|

By Rolf Charlston, Philadelphia

Pamela King, “Like

painting, like music...”: Joseph Conrad and the Modernist

Sensibility. Nathan, Queensland: Coop Bookshop, 1996.. xii+116

pp.

The intention of this slim work is to recognize

Conrad’s Modernist sensibility in the context of the arts.

Conrad asserts in the “Preface” to The

Nigger of the “Narcissus” that fiction is “like

painting, like music,” and King’s thesis is that Conrad

was aware of emerging artistic currents; that correspondences exist

between these artistic issues and his biography; and that these

correspondences define him as a writer. Her intention is worthy,

but the substance is largely derivative.

With 87 references in the endnotes for the

sixteen pages of the first chapter, King establishes in typical

graduate-student fashion the derivative nature of her work with

a survey of the critical literature about Conrad and the Modernist

sensibility.

This reads like a Master’s thesis –

which it is – or, as the author acknowledges, her thesis at

Griffith University in Australia became the “catalyst”

for this volume. The review covers biography, culture, art, music,

film, the aesthetic movement of art for art’s sake, and some

of Conrad’s writing like A

Personal Record and the “Preface” to The

Nigger.

While references from Rodin to Zdzislaw Najder

abound in Chapter 2, “Conrad’s Early Cultural Formation,”

some fresh ideas do emerge in King’s reading of The

Arrow of Gold (1919). Oddly, she extensively (for her) discusses

this late work in this chapter. But she does so perceptively, showing

how Conrad fuses classical, romantic, and realistic impulses with

references to the visual arts in his continuing attempt to discover

a “New Form” of the novel. Allégre’s evocation

of the Byzantine Empress Theodosia, Cabanel’s organic painting

of Venus, and the representation of Rita as “a padded sculptural

realistic dummy” contribute to the complex characterization

of Rita.

The heart of “Like painting, like music...”

is the analysis of three major works: “Heart of Darkness,”

Nostromo, and The

Secret Agent, with a chapter devoted to each. After two chapters

of biographical, historical, and critical background, one expects

finally to plunge into a close reading of the art in a Conrad text,

especially in the chapter entitled “Heart of Darkness.”

But like the “delayed decoding”

Ian Watt writes of and to which King refers, the discussion of this

novella is again delayed. She begins, instead, by returning to her

background topic in Chapter 1, namely, Conrad’s affinity with

the Modernist movements of Impression and symbolism.

It is almost as if this chapter on “Heart

of Darkness” had previously been a discrete paper. King repeats

fundamental observations on “Heart of Darkness” –

observations regularly made in undergraduate classes – but

does so under the rubrics of art: light and dark imagery; a sculptural

Buddha; painterly and sculptural references to ivory, bones, and

skulls; images of African works of art; the two contrasting paintings

like icons of women, the one apparently by Kurtz, the other of Queen

Victoria. King’s achievement is to organize these observations

into artistic categories.

In dealing with Nostromo,

King introduces aspects of the Modernist sensibility appropriate

to the writing of the novel, particularly the concept of time and

the emergence of cinema. Acknowledging other critics, she states

that Conrad frequently appears to reflect awareness of many Bergsonian

ideas, like “homogeneous time” (54), durée,

and a Fourth Dimension.

Drawing on the distinction between “blurred”

and “hard” reality in Conrad’s narrative experiments,

as related by Frederick R. Karl, King explicates Conrad’s

“literary impressionism” (58). An application in Nostromo

is that solidly defined visual art objects, like architectural

and sculptural elements and lithographs and watercolours, contrast

with the movement in time, both backwards and forwards, of the characters’

words. The blurred movement is like an Impressionist painting.

When she goes beyond Karl and other critics,

she is at her forte, focusing upon “impressionist traits”

in order to trace “correspondences between modernist art and

Conrad’s literary modernism” (58). She looks at the

art objects in Nostromo –

the statue of Charles IV, statues of the Madonna, Emilia’s

watercolours, Parochetti’s sculpture, and the cathedral altarpiece

– and recognizes the “active patterning” in the

sequence of these images, “a dynamic impression of movement”

(53) and the “cinematic orchestration of its central images”

(56). These images in the context of reality’s Fourth Dimension,

King concludes, seem “quintessentially modernist” (67).

Prompted by other critics, King considers music

in The Secret Agent, especially

the two pianos, and Bergson’s Fourth Dimension of time. When

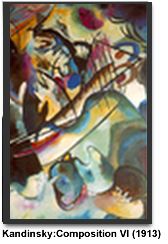

she views the art and writing of Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944),

however, she establishes some striking resemblances with Conrad

and does so independently. She suggests no direct influence between

the artist and the novelist, as Kandinsky’s texts are Concerning

the Spiritual in Art (1911-12) and

Point and Line to Plane (1926).

King does assert that Bergson, Conrad, and

Kandinsky “overlap” in their emphasis on simultaneity

and Fourth-Dimensional space (74). “In Summer” (1904)

and “Composition IV” (1911) illustrate the aesthetic

resonances between Kandinsky’s art and The

Secret Agent. Portrayed realistically in In

Summer, a woman and little girl with a hoop divide the picture

plane diagonally and vertically and suggest to King a walking movement

frozen in time. In the abstract “Composition IV,” linear

motifs combine with geometric areas of colour and form and suggest

life and energy captured in perpetuity.

King’s drawings throughout the book,

that reproduce the art of others, are, at best, charming. Here,

however, she superimposes lines upon her interpretations of these

two Kandinsky works. The geometrical lines on In

Summer indicate the implied abstract forces of energy and

movement; the lines on “Composition IV” emphasize Kandinsky's

abstractions. In these cases the drawings contribute to King’s

position.

While Kandinsky’s art becomes wholly

abstract, in The Secret Agent

Conrad combines the literal and the abstract. While Conrad contrasts

circular and triangular motifs, the first associated with Stevie

and the second with Verloc, King points out that Kandinsky identifies

these forms as “the primary pair of planes,” and she

suggests that the two artists shared the same basic, visual logic.

She maintains that the geometrical and musical images or motifs

in The Secret Agent and in

Kandinsky’s mature, abstract paintings “typify the highly

analytical interdisciplinary … impulse informing the modernist

sensibility” (81).

King concludes with a two-page chronological

table of events in Conrad’s life and times including, for

example, the publication in 1867 of Das

Kapital and the outbreak of the First World War. This table

returns the volume to a basic level.

The provocative discussion of Conrad and Kandinsky,

on the one hand, and the simple chronological table, on the other,

demonstrates this work's inconsistency. Much of the volume is derivative

or obvious. Attempting to cover too much in a limited space, King

becomes a skimmer of a sea of material. Her strength, however, is

her analysis of Nostromo and,

especially, The Secret Agent where

she reveals her experience as an art critic for ten years and writes

with independent self-confidence.

© 2005 Rolf Charlston

|