|

By J. H. Stape, Vancouver

Wieslaw Krajka, editor.

A

Return to the Roots: Conrad, Poland, and East-Central Europe.

Conrad Eastern and Western Perspectives, Vol. 13. Boulder/Lublin:

Distributed by Columbia University Press, 2004. viii + 308. $50.

Conrad's relationship to his cultural background

is a story of unremitting complexity. Born in the Ukraine of Polish

parents, he was from birth a figure at the margins. His parents’

life experience in what on today’s map is “Poland”

was brief, as was his, growing up as he did partly in the area near

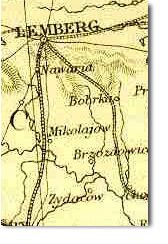

Kiev, in Russian exile, then in the Austro-Hungarian city Lemberg

(now in Ukraine), and leaving Eastern Europe at the age of sixteen

for Marseilles and the wide world. The son of political activists,

Conrad claimed that his first memory was of visiting his father

in Warsaw’s citadel.

The relationship of Poland to Conrad has been

no less fraught: in 1898, when he was barely scraping a living from

fiction published in a couple thousand copies, a Polish novelist

attacked him for writing “popular and very lucrative novels”

for the English market instead of giving his talents to Polish literature.

More subtle or more informed views have not always prevailed since.

In the 1930s, Gustav Morf worked up a crude theory of betrayal of

the fatherland on the basis of Lord

Jim.

On the topic of Conrad and Poland, Conrad

studies continue to suffer imbalances, erasures, and blind spots.

Facts to the contrary, Conrad has been claimed for Catholicism,

and Zdzislaw Najder’s 1983 biography not accidentally refers

to Lemberg as Lvóv. Coded readings are something of a mini-industry:

fiction set in Southeast Asia and South America is “really”

about Poland and fanciful “evidence” for this presented;

“Amy Foster,” whose protagonist dies in a ditch, is,

after sufficient distortions, “about” Polish Messianism.

Conferences in Poland follow in “Conrad’s

Polish footsteps.” Those of The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

are usually held, by longstanding arrangement, at London’s

Polish Social and Cultural Centre. Polonitis, like avian flu, is

catching: the word “exile” is regularly and inappropriately

evoked for a man who took up British nationality and identity by

choice in his maturity, and Daniel R. Schwartz can write, at the

outer margins of the fantastic, of Conrad’s “life-long

desire” to return to Poland.

This selection of fourteen papers from a conference

held in Poland in 2001, usefully avoiding extremist positions, focuses

on three main topics: Conrad’s reception by several Polish

writers, the short story “Amy Foster,” and Conrad and

Russian literature. It opens with Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek’s

greeting to the conference (politics and writing are still deadly

serious business in Eastern Europe), followed by an overview of

the volume’s contents by the editor. It closes with two indices

– one to non-fictional names, the other to Conrad’s

work.

The first clutch of essays is mainly of specialist

interest. Wieslaw Krajka focuses on Kapitan Conrad, a six-part Franco-Polish

docu-drama made in 1990, presenting Conrad and his father, the poet

and dramatist Apollo Korzeniowski, as “martyrs” for

the Polish nationalist cause. Much of the essay inevitably describes

scenes in the film, with a running commentary on their ideological

biases. Krajka concludes that the writers freely lurched from fact

to fiction in pursuit of their polemical aims, bolstering (although

he does not say this) an emergent and newly challenged Polish identity

at the period when the rusty and creaking Iron Curtain was falling.

Amar Acheraïou in “The Shadow of

Poland” ranges more widely, locating a suppressed Poland in

Conrad’s fiction. He deftly assays an absence-is-presence

theme, but could have justifiably seen “Poland” less

monolithically. (There were, in effect, various Polands or constructions

of a nation that was a state of mind rather than a nation-state.)

Donald W. Rude uncovers a 1919 interview with a Polish journalist,

published in Chicago in 1924. He is wrong in claiming that this

was Conrad’s second interview (another having occurred during

his 1914 visit to Poland): a Daily

Mail journalist went down to The Pent in July 1901 for just

such a purpose (see CL 2:

340).

More skepticism as to the degree that Conrad

shaped his comments about Polish politics for his interviewer and

future audience might have been applied. Interested in the fate

of Poland at the close of the First World War, Conrad systematically

kept a discreet distance from Polish organizations in London. Not

indifferent to public affairs generally, he did write essays on

the topic and also, for instance, pronounced on women’s suffrage

and dramatic censorship.

Three essays explore the responses to Conrad

by figures prominent on the Polish literary scene of their day but

little known to the English-speaking world: that of the dramatist

and novelist “Witkacy,” the critic and drama theoretician

Jan Kott, and the journalist Antoni Golubiew. These essays focus

on the politico-ideological crosscurrents in the Polish reception

of Conrad, ranging from Witkacy’s nuanced admiration, to Jan

Kott’s rejection of a bourgeois decadent purveying despondency,

to Golubiew’s brightly tinted appreciation of Catholic values

in Conrad’s work.

Of the three essays marking the centenary

of the publication of “Amy Foster” that by Mary Harris

is the most probing. After a taut review of biographically-oriented

criticism, she goes on to argue for seeing the background of Amy

and the inhabitants of the Kentish setting as important as those

of the exotic protagonist-outsider Yanko Goorall. Despite Conrad’s

hostility to Christianity -- “I always, from the age of fourteen,

disliked the Christian religion, its doctrines, ceremonies and festivals”

(to Edward Garnett, 22 December 1902) -- Yannick Le Boulicault of

the Université catholique d’Angers, unconvincingly

acclaims Yanko a Christ figure.

Anna Brzozowska-Krajka, developing earlier

work, goes for intertextuality, adducing the influence of the Polish

Romantic tradition generally, and, more specifically, of Józef

Korzeniowski’s 1843 play Carpathian Mountaineers on the story.

The romanticization of the Carpathian highlander is found in several

texts of the period, and the case seems partly to rely on Conrad’s

awareness of a writer from a previous generation whose name he happened

to bear.

The Central Europe of the volume’s title

is hardly touched on, unless Russia, oddly, stands in for it. “Conrad

and Russia” forms a focus of interest for four critics, who

variously consider the writer’s relationship with the work

of Dostoevsky and Turgenev. Harry Sewlall focuses on Under

Western Eyes and Crime and

Punishment, drawing on a large body of criticism and on the

theoretical stances of Bakhtin and Julia Kristeva to place the two

works into fruitful juxtaposition.

Monika Majewska expands on previous work, arguing

that Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin and Nastasya Filippovna of

The Idiot influenced Conrad’s

Stevie and Winnie in The Secret Agent. The essays on Conrad and

Turgenev -- by Katarzyna Sokolowska on images of nature in the two

writers and Brygida Pudelko who adduces the influence of The

Sportsman’s Sketches (here called The

Sportsman’s Notebooks) on the loose structure of The

Mirror of the Sea -- necessarily make less than watertight

cases as influence studies often do, although both contain interesting

individual observations.

The conference seems to have generated surprisingly

little in the way of biographical or other “hard” scholarship,

where linguistic skills and matchless proximity to sources otherwise

difficult of access allow native Polish speakers to make particular

contributions. One assumes that despite the four decades of Zdzislaw

Najder’s meticulous and richly rewarded efforts and the patchy

survival of archives in a country plagued by strife there are still

things to turn up. Like most collections of conference papers, and

like conferences themselves, this is an occasion of mixed pleasures.

© 2005 J. H. Stape

|